Spoiled and Sullied . . . by Joel Mann

My whole family hails from Wisconsin. As such, we’re all Green Bay Packer fans. Prior to writing this, I had to watch in stunned disbelief as my team choked on a near certain trip to the Superbowl, going down in inglorious defeat after they had outplayed Seattle all afternoon. It’s quite the humbling end to potentially great year. Why do I bring this up? It reminded me of the all the ways that Mother Nature attempts to spoil and sully a perfectly good glass of wine, sending an otherwise valuable vintage year down the drain. So in honor of my team’s best Mama Cass impression, I’m bringing you some of the strange and odd ways that a wine can make you want to choke.

There are numerous unwanted microbes capable of growing in grape juice. The desired Saccharomyces cerevisiae typically takes over quickly though, especially when inoculated. Most microbes will not survive in fermented wine as the combination of high alcohol, pH, osmotic stress, and inhibiting factors that Saccharomyces gives to wine is a rather toxic environment to their survival. It’s not uncommon to have spoilage agents grow on the surface of improperly stored wines though, as a small amount of nutrient substrate remains in completed fermentations. With a little unintended oxygen, no SO2, and the right conditions, growth can take hold. Certain species of Pichia and Candida yeast can form a white scum on the surface which has a cheese-like appearance. With Candida it’s mostly a cosmetic problem, but Pichia can give your wine the rather unpleasant aroma and taste of nail polish remover from the ethyl acetate it produces.

One spoilage agent dubbed by textbooks as the “winemaker’s nightmare” is Saccharomyces ludwigii. It has a high resistance to all the factors that cause other microbes to die off in fermentation. Luckily, it’s a rare bug to contract. It gives wines a strong oxidized/Sherry flavor from producing excess amounts of acetaldehyde, in addition to leaving what is described as a slimy texture to the beverage. Sounds rather appetizing, no?

One of the controversial agents is Brettanomyces. It’s a yeast capable of surviving in fermented wines and can produce a wide range of flavor compounds in doing so. The controversy is that some of those flavors can be pleasant – earthiness, smoke, hints of leather and creosote, or subtle spice notes. The problem is that brett (as it’s called in the industry) can also contribute far less pleasant characters described as sweaty horse blanket, wet dog, barnyard, and band-aid. While the smell of creosote in the desert after the rain may be enjoyable, the wet dog who was out in the rain as well is not.

One spoilage that’s rare to come across is ropiness. It’s the formation of a slimy, viscous, egg-white consistency growth in the wine. When it occurs, you can literally place an object in the wine and draw out a long, slimy rope that attaches itself. It almost looks like that trail which attaches itself to your spoon when you scoop out a thick honey or molasses. The problem is, it’s not something sweet you’d like to put in your mouth. The ropey slime is believed to come from dextran formation by Leuconostoc bacteria, but the underlying holistic cause of the fault may be a series of microbial contaminants acting in concert.

Another curious spoilage is the development of what’s called mousey character. The spoilage basically gives the wine the aroma of a mouse nest or mouse urine. It’s an aroma that comes from a group of piperidines/pyridines that form as the oxidation products of the amino acid lysine. Lysine is not metabolized by Saccharomyces yeast, but other microbes, particularly Brettanomyces and two common Lactobacillus, can process the compound, and are suspected in the formation of the fault.

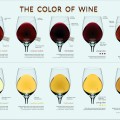

The last strange fault I have space to address is acrolein spoilage. Acrolein is the simplest form of unsaturated aldehyde, with a bit of a piercing, acrid smell. It’s produced by lactic acid bacteria. By itself, it’s nothing special, as its minute concentrations in wine would not be noticeable. It has a tendency to react with other compounds in rather unpleasant manners though. In wine it reacts with different phenolic groups on anthocyanins (the compounds that give wine color) resulting in intensely bitter flavors. It’s the old bitter beer face, but with your vino instead.

While the Pack may have crashed and burned in rare fashion, here’s hoping you avoid these rare faults as you’re out enjoying a nice glass of wine.

Drink responsibly.